Free shipping

No products in shopping cart

Continue shopping

Water veins run underground. When we think about the water cycle on earth, we usually think about rain, rivers, lakes, and the sea. Rivers, lakes and the sea make up the Earth’s surface water. But there is also a great deal of water underground. Rainwater seeps into the ground and continues its journey underground. If it doesn’t resurface as spring water, then it collects underground to form bodies of groundwater.

It isn’t possible for us to know precisely how the negative effects of water veins work. But models can give us some idea. One common explanation is that, as water flows between layers of rock underground, it produces friction. In turn, these layers of rock produce electric fields, especially when they are under high pressure. These electric fields then cause interference with the natural magnetic field of the Earth and produce “turbulence.” The radiation fields from this turbulence then expand beyond the Earth’s surface. Another explanation is that the high pressure of the water flowing underground causes the release of ions, which are then sent upward.

Water veins are highly energizing—even brief exposure has a strong effect on us. In small doses, exposure can be invigorating. In excess, however, exposure can be detrimental not only to humans but to all living things. For example, some research studies have indicated that it can cause spiral growth and proliferation in trees as well as scoliosis and cancer in humans (Baker-Laporte et al., 2008, 65-66; Teitze, 1997, 58; Saunders, 2003; Croome, 1994).

Water veins are located at depths of between 15 – 1000 meters underground. Their effect depends on their size and distance from the Earth’s surface. But even the deepest water veins can impact life above ground. If your home is located over a water vein, the electric field of the water vein will have an effect throughout the home or building even though its intensity can vary between rooms and floors.

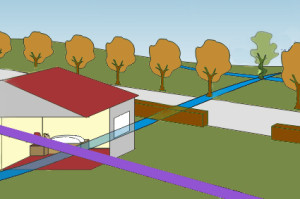

Our basic understanding of water veins is that they join together when they meet, forming a broader stream. But, because there are multiple layers of rock in any given place, they can also intersect without joining. As we discuss above, water veins exist at varying depths. This difference in depth allows them to crisscross. Additionally, depending on the inclination of the rock layer, they can flow in different or even opposite directions. As the picture above illustrates, if we could see through the layers of rock, these intersecting veins would form a cross.

At the point where these water veins intersect, the effect of the water veins on the Earth’s surface increases significantly and may accelerate the progression of disease.

In some areas, water veins are more frequent and their effect is stronger. This is especially true for regions with regular rainfall. Water veins are particularly prevalent in mountain areas such as the Alps or the Rockies.

Water veins are less common in arid zones, although appearances can be deceptive.

In the Sahara, for example, water veins are common in the vicinity of wadis, riverbeds which hold water during the rainy season. In addition to the surface water or rainwater held in these riverbeds, The Sahara also contains vast underground aquifers. Geologists refer to this water as “fossil groundwater.” The Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System, one of the two aquifers in the Sahara, is one of the largest in the world. It covers just over 2.2 million km2, spans four countries, and contains approximately 375,000 km3 of water (Ahmed, 2013, 114; Nubian Aquifer Project). Additionally, a recent study by the British Geological Survey estimates “total groundwater storage in Africa to be 0.66 million km3” with anywhere from 3,770 to 21,400 km3 in the Western Sahara alone (MacDonald et al., 2012; Thornhill, 2012).